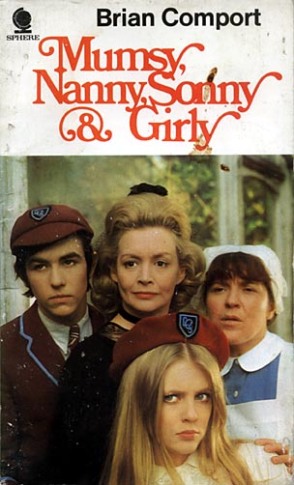

At the end of the 60s, ‘anti-psychiatrist’ R D Laing’s ideas about the family as an oppressive institution causing untold psychological damage to its members started to filter down into popular culture. Makers of horror films took them up with particular aplomb, and in the 70s unhealthy family relationships become as much of a horror cliché as fog-shrouded graveyards were in previous decades. They’re at the centre of some of the most interesting British horrors of the time, including Mumsy, Nanny, Sonny and Girly; Goodbye Gemini; Demons of the Mind; The Creeping Flesh; Frightmare – and this little curio.

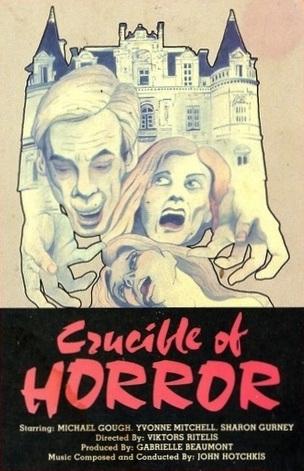

An arty, small-scale project, it was the brainchild of director Viktors Ritelis and actor Olaf Pooley, who wrote it and also pops up as a suspicious neighbour. The film’s original title was The Corpse. That’s a creepy and appropriate enough title but in their infinite wisdom the film’s American distributors retitled it Crucible of Horror (“crucible” is one of those words that sounds good in a horror film title even if it doesn’t have much to do with the film: see also the Mike Raven extravaganza Crucible of Terror – although that was called Unholy Terror in the US).

Michael Gough gives a pretty restrained performance (by his standards) as domestic tyrant Walter Eastwood. The first indication we get that his relationship with his teenage daughter Jane (Sharon Gurney) is a bit out of the ordinary is the sight of him furtively squeezing her bike seat shortly after she’s dismounted.

The second is the sight of him beating her senseless with a riding crop after learning she’s stolen money from the local golf club (and aroused the interest of its lecherous proprietor).

Jane gets no sympathy from her brother Rupert, an odious creep who idolises his father despite or because of his general terrorising of the family (and is played by Gough’s real-life son Simon). Mother Edith (Yvonne Mitchell) retreats from her nightmarish home life into her room, where she paints monstrous portraits of Walter.

The family’s strained dinner table conversation, full of subtle putdowns that wouldn’t be out of place in an Ivy Compton-Burnett novel, makes for uneasy viewing. “Oh God,” says Rupert, on realising he’s forgotten to buy a canvas for his mother. “I hardly think He would be interested”, Edith replies with subtle self-pity. Her face perfectly communicating a lifetime of disappointment, Mitchell’s brilliant performance is the heart of the film: Edith’s faraway manner conceals a burning hatred for her husband that quietly comes to a head after the assault on Jane. “Let’s kill him,” she says to her daughter at breakfast the morning after, and it’s her lack of emotion that makes it such a heartrending moment.

Edith and Jane follow Walter on a shooting weekend at the family’s country retreat, where Edith shoots her husband after explaining she’s been inspired by reading the Marquis de Sade in an effort to understand how his mind works: “it’s full of the most unutterable filth, but it opened a few windows for me”. Walter’s fear of his impending death is outweighed by his sheer outrage that his wife would dare handle one of his firearms. The women’s efforts to make the death look like an accident afford us the sight of a half-naked Michael Gough, something perhaps few people have ever wanted to see.

But Walter proves no easier to handle in death than he did in life, his body disappearing and reappearing in disturbing fashion, leading to a creepy and entirely inexplicable conclusion. Meanwhile, Edith’s decaying mental state’s conveyed to us through the kind of psychedelic dream sequence that’s always a highlight of films from this era.

This probably isn’t everyone’s idea of a classic horror film: anyone drawn in by the title and John Hotchkis’s utterly generic horror music (it sounds more like the theme to Dark Shadows than anything else) might be driven up the wall by the self-conscious artiness, the many talky scenes and the lack of any especially gruesome moments, let alone the lack of explanation for the strange goings-on. But it’s a disturbingly pessimistic portrait of middle-class family life as an inescapable prison, with a steadily mounting atmosphere of dread.

The current US DVD release of Crucible of Horror has absolutely diabolical picture quality, and the sound’s no better. If ever an obscure British film deserved to be given a brush-up by the BFI’s Flipside department it’s this one.

Oh, and even more inexplicable than the film’s ending is the presence of this in the Eastwood home:

Yes – it’s a Michael Gough mask! Why these aren’t readily available in the shops is beyond me: I don’t know about you but I now want one of these more than anything else on Earth.

tendencies. They’re all direct descendants of Psycho and Peeping Tom, but it’s in Twisted Nerve the lineage is most obvious: Peeping Tom’s writer Leo Marks co-wrote the Twisted Nerve screenplay with Roy Boulting (Mills and Bennett’s relationship in Twisted Nerve’s vaguely reminiscent of Carl Boehm and Anna Massey’s in the older film), and like Psycho it’s got an unforgettable score by Bernard Herrmann. In fact, Herrmann’s haunting, whistled theme is far better known than the film itself, having been given a new lease of life by Quentin Tarantino’s use of it in Kill Bill (and, more recently, it was heavily featured in the first series of American Horror Story). It turns up here in several variations, including a wonderfully silly party version and a slowed down, oddly circus-like version used for the film’s denouement.

tendencies. They’re all direct descendants of Psycho and Peeping Tom, but it’s in Twisted Nerve the lineage is most obvious: Peeping Tom’s writer Leo Marks co-wrote the Twisted Nerve screenplay with Roy Boulting (Mills and Bennett’s relationship in Twisted Nerve’s vaguely reminiscent of Carl Boehm and Anna Massey’s in the older film), and like Psycho it’s got an unforgettable score by Bernard Herrmann. In fact, Herrmann’s haunting, whistled theme is far better known than the film itself, having been given a new lease of life by Quentin Tarantino’s use of it in Kill Bill (and, more recently, it was heavily featured in the first series of American Horror Story). It turns up here in several variations, including a wonderfully silly party version and a slowed down, oddly circus-like version used for the film’s denouement. Aside from the music, the best thing about the film is Bennett’s remarkable performance. Martin’s a spoilt, indolent rich kid who nonetheless is haunted by the fate of his older brother, placed in an institution by their mother (Phyllis Calvert), unable to cope with (but mostly just embarrassed by) his Down’s Syndrome (or ‘mongolism’, in the now rather awkward 60s terminology). When we first see him, visiting his brother, he seems like a perfectly ordinary young man. Next time we meet him, he’s disconcertingly different. He’s invented another persona, the childlike ‘simpleton’ Georgie, which he uses to charm library assistant Susan (Hayley Mills), and, when his exasperated stepfather’s had enough and chucks him out (which eventually Martin takes bloody revenge for), to inveigle his way into her home. Bennett is convincingly innocent as Georgie, and his sudden switches to snarling, dangerous Martin are truly chilling. The split personality angle’s heavy-handedly underlined by his tendency to strip off and fondle himself in front of a mirror. There’s a stack of musclemen magazines nearby to act as a casually homophobic signal that he’s a bit odd sexually.

Aside from the music, the best thing about the film is Bennett’s remarkable performance. Martin’s a spoilt, indolent rich kid who nonetheless is haunted by the fate of his older brother, placed in an institution by their mother (Phyllis Calvert), unable to cope with (but mostly just embarrassed by) his Down’s Syndrome (or ‘mongolism’, in the now rather awkward 60s terminology). When we first see him, visiting his brother, he seems like a perfectly ordinary young man. Next time we meet him, he’s disconcertingly different. He’s invented another persona, the childlike ‘simpleton’ Georgie, which he uses to charm library assistant Susan (Hayley Mills), and, when his exasperated stepfather’s had enough and chucks him out (which eventually Martin takes bloody revenge for), to inveigle his way into her home. Bennett is convincingly innocent as Georgie, and his sudden switches to snarling, dangerous Martin are truly chilling. The split personality angle’s heavy-handedly underlined by his tendency to strip off and fondle himself in front of a mirror. There’s a stack of musclemen magazines nearby to act as a casually homophobic signal that he’s a bit odd sexually. Susan’s the only person Martin shows any sexual interest toward though – although her slightly tarty mother Joan (Billie Whitelaw) meets a sticky end after a clumsy attempt at seducing him. The sight of Susan helping to dress a clearly aroused Martin, secure in the belief he’s completely unsexual, is the film’s queasiest moment, but dodgy as the premise of someone pretending to be learning disabled might seem, the main problem with the film is that it’s not offensive enough. It’s far too restrained and genteel, and despite its obvious channelling of Hitchcock (most bizarrely when, in an echo of the ending of Psycho, Hywel Bennett starts speaking in the badly dubbed voice of Phyllis Calvert) it’s seriously lacking in suspense. Interestingly, as well as echoing one Hitchcock film, Twisted Nerve foreshadows another: Barry Foster’s Gerry, Joan’s lodger/lover, is an only slightly more benign version of Bob Rusk, the jolly psycho he plays in Frenzy. Gerry works for a film distributor (presumably based in Soho), and is a type you can sense Twisted Nerve’s makers looking down their noses at: “If you want me to sell your crummy films, you’ve gotta give it a dose of the old S&V – sex and violence! Cartoon, ice cream, the old S&V, and everyone’s happy.” If Gerry had been involved with the making of Twisted Nerve it probably wouldn’t look or sound as good, and it certainly wouldn’t have such a top-drawer cast. But I can’t help thinking it would have been a lot more lively.

Susan’s the only person Martin shows any sexual interest toward though – although her slightly tarty mother Joan (Billie Whitelaw) meets a sticky end after a clumsy attempt at seducing him. The sight of Susan helping to dress a clearly aroused Martin, secure in the belief he’s completely unsexual, is the film’s queasiest moment, but dodgy as the premise of someone pretending to be learning disabled might seem, the main problem with the film is that it’s not offensive enough. It’s far too restrained and genteel, and despite its obvious channelling of Hitchcock (most bizarrely when, in an echo of the ending of Psycho, Hywel Bennett starts speaking in the badly dubbed voice of Phyllis Calvert) it’s seriously lacking in suspense. Interestingly, as well as echoing one Hitchcock film, Twisted Nerve foreshadows another: Barry Foster’s Gerry, Joan’s lodger/lover, is an only slightly more benign version of Bob Rusk, the jolly psycho he plays in Frenzy. Gerry works for a film distributor (presumably based in Soho), and is a type you can sense Twisted Nerve’s makers looking down their noses at: “If you want me to sell your crummy films, you’ve gotta give it a dose of the old S&V – sex and violence! Cartoon, ice cream, the old S&V, and everyone’s happy.” If Gerry had been involved with the making of Twisted Nerve it probably wouldn’t look or sound as good, and it certainly wouldn’t have such a top-drawer cast. But I can’t help thinking it would have been a lot more lively.

Young women are being stabbed to death in London by a mysterious man clad in leather. The case is being investigated by Detective Inspector Rowan (Gilbert Wynne) and becomes very personal when his wife (Linda Marlowe) falls victim to the killer. She’s knifed in the shower, which is a bit of a mistake because the last thing an extremely modest film like this should be doing is reminding people how good Psycho was. Anyway, Rowan begins a vendetta against cocky scofflaw Pete Laver (Donald Sumpter), who he’s convinced is the man responsible. Laver’s attitude to the opposite sex is pretty repellent (“makin’ birds is like a career with me… I bang every bird I meet” – that’s an example of the ridiculous dialogue he gets throughout), but he’s not the only suspect.

Young women are being stabbed to death in London by a mysterious man clad in leather. The case is being investigated by Detective Inspector Rowan (Gilbert Wynne) and becomes very personal when his wife (Linda Marlowe) falls victim to the killer. She’s knifed in the shower, which is a bit of a mistake because the last thing an extremely modest film like this should be doing is reminding people how good Psycho was. Anyway, Rowan begins a vendetta against cocky scofflaw Pete Laver (Donald Sumpter), who he’s convinced is the man responsible. Laver’s attitude to the opposite sex is pretty repellent (“makin’ birds is like a career with me… I bang every bird I meet” – that’s an example of the ridiculous dialogue he gets throughout), but he’s not the only suspect. Judge Charles Lomax (sepulchural-voiced Jack May, best known to my generation at least as the voice of Igor in Count Duckula and hamming it up a treat here) is a “modern witchfinder” obsessed with putting a stop to “the filth and horror of the age”. He hands out grotesquely disproportionate sentences to defendants he views as morally unsound and has a near breakdown after delivering each verdict. Could he have taken to handing out rough justice of his own? Then there’s his clerk, Carter (Terry Scully, whose shifty appearance is perfectly used here) whose ringing denunciations of the permissive society draw even Lomax’s disdain for their extremity, but who spends his spare time goggling at porn mags and pawing at strippers in the fleshpits of Soho.

Judge Charles Lomax (sepulchural-voiced Jack May, best known to my generation at least as the voice of Igor in Count Duckula and hamming it up a treat here) is a “modern witchfinder” obsessed with putting a stop to “the filth and horror of the age”. He hands out grotesquely disproportionate sentences to defendants he views as morally unsound and has a near breakdown after delivering each verdict. Could he have taken to handing out rough justice of his own? Then there’s his clerk, Carter (Terry Scully, whose shifty appearance is perfectly used here) whose ringing denunciations of the permissive society draw even Lomax’s disdain for their extremity, but who spends his spare time goggling at porn mags and pawing at strippers in the fleshpits of Soho. Night, After Night, After Night is not, in itself, a very fulfilling film (unless, perhaps, you’re especially keen on long scenes of heavy petting) but it’s an interesting one in terms of its place in British horror cinema. It revives the themes of Cover Girl Killer and Peeping Tom from ten years before but also looks ahead to the corrupt moral guardians of Pete Walker’s House of Whipcord and House of Mortal Sin. In fact, watching Night, After Night, After Night I found myself regularly thinking how much more frightening and wittier it would have been with Walker and his screenwriter David McGillivray behind the scenes. It can also be seen in terms of a sort of crude British version of the Italian giallo film. That seems almost an inherently funny idea, British filmmakers’ attitudes to sex and violence being generally so different from Italians’ – and certainly Night, After Night, After Night has no trace of the stylishness that makes gialli interesting. But while its killer doesn’t wear black leather gloves, he wears black leather everything else, and its plot’s as easy to imagine unfolding in the glamorously violent world of Dario Argento and his compatriots as it is against the grottier backdrop of a Butcher’s B-feature. Of course if it was a giallo it would need a far more absurd title: in deference to the most eccentric part of the murderer’s get-up it would surely have to be Death Wears a Beatle Wig.

Night, After Night, After Night is not, in itself, a very fulfilling film (unless, perhaps, you’re especially keen on long scenes of heavy petting) but it’s an interesting one in terms of its place in British horror cinema. It revives the themes of Cover Girl Killer and Peeping Tom from ten years before but also looks ahead to the corrupt moral guardians of Pete Walker’s House of Whipcord and House of Mortal Sin. In fact, watching Night, After Night, After Night I found myself regularly thinking how much more frightening and wittier it would have been with Walker and his screenwriter David McGillivray behind the scenes. It can also be seen in terms of a sort of crude British version of the Italian giallo film. That seems almost an inherently funny idea, British filmmakers’ attitudes to sex and violence being generally so different from Italians’ – and certainly Night, After Night, After Night has no trace of the stylishness that makes gialli interesting. But while its killer doesn’t wear black leather gloves, he wears black leather everything else, and its plot’s as easy to imagine unfolding in the glamorously violent world of Dario Argento and his compatriots as it is against the grottier backdrop of a Butcher’s B-feature. Of course if it was a giallo it would need a far more absurd title: in deference to the most eccentric part of the murderer’s get-up it would surely have to be Death Wears a Beatle Wig. The puzzle pieces dished out to us: a runner (played, fans of cult TV may be interested to know, by Nigel Lambert, who did the voiceover for spoof schools programme Look Around You) collapses in central London and wakes to find himself in a private hospital ward complete with sinister/sexy nurse, and a new limb amputated every time we cut back to him (wonderfully bizarre, this). Also in London, Superintendent Bellaver (Alfred Marks) is investigating the murder of a girl whose body was drained of blood. The trail leads to her employer, the rather shifty Dr Browning (Vincent Price). And in an unnamed militaristic state (presumably in Eastern Europe somewhere) the seemingly superhuman Konratz (the rather wooden Marshall Jones, hilarious later in the film stalking the streets of London in a bobble hat) is letting nothing and nobody stand in the way of him seizing power, disposing of superiors who get in his way (including Peters Cushing and Sallis) with a deadly shoulder squeeze.

The puzzle pieces dished out to us: a runner (played, fans of cult TV may be interested to know, by Nigel Lambert, who did the voiceover for spoof schools programme Look Around You) collapses in central London and wakes to find himself in a private hospital ward complete with sinister/sexy nurse, and a new limb amputated every time we cut back to him (wonderfully bizarre, this). Also in London, Superintendent Bellaver (Alfred Marks) is investigating the murder of a girl whose body was drained of blood. The trail leads to her employer, the rather shifty Dr Browning (Vincent Price). And in an unnamed militaristic state (presumably in Eastern Europe somewhere) the seemingly superhuman Konratz (the rather wooden Marshall Jones, hilarious later in the film stalking the streets of London in a bobble hat) is letting nothing and nobody stand in the way of him seizing power, disposing of superiors who get in his way (including Peters Cushing and Sallis) with a deadly shoulder squeeze. The international intrigue elements of the film are a bit dull – the London sections are much more interesting, greatly benefiting from a droll performance from Marks, playing one of a long line of disgruntled detectives who pop up in British horror films. The gold standard is Donald Pleasence in Death Line, but Marks’ splendidly gruff Bellaver comfortably takes silver. The film’s most memorable character, however, is the mysterious Keith (Michael Gothard) the man behind the vampire murders (sorry for the spoiler, it’s not much of one). A louche dandy with an enormous blond bouffant and ruffled purple satin shirt, he’s the world’s most Swinging 60s looking person. We initially encounter him in the regulation 60s nightclub scene, which is pretty impressive here – the club looks huge and it’s chock-full of people dancing extremely self-consciously in wonderfully absurd outfits. The Amen Corner (of “If Paradise is Half as Nice” fame) are on stage, and their set obligingly includes a catchy number called “Scream and Scream Again”. However, a few rather too close shots of the singer reveal he’s not even opening his mouth. This club is where Keith picks up his victims, who he then brutally rapes and kills. One of them turns out to be an undercover policewoman, and this leads to the film’s main set piece, an incredibly long but pretty absorbing chase sequence that dominates the whole middle section of the film. This sequence is so lengthy compared to the head-spinning speed of the first part of the film that it throws Scream and Scream Again off balance, with scarcely half an hour left to explain what the hell’s going on.

The international intrigue elements of the film are a bit dull – the London sections are much more interesting, greatly benefiting from a droll performance from Marks, playing one of a long line of disgruntled detectives who pop up in British horror films. The gold standard is Donald Pleasence in Death Line, but Marks’ splendidly gruff Bellaver comfortably takes silver. The film’s most memorable character, however, is the mysterious Keith (Michael Gothard) the man behind the vampire murders (sorry for the spoiler, it’s not much of one). A louche dandy with an enormous blond bouffant and ruffled purple satin shirt, he’s the world’s most Swinging 60s looking person. We initially encounter him in the regulation 60s nightclub scene, which is pretty impressive here – the club looks huge and it’s chock-full of people dancing extremely self-consciously in wonderfully absurd outfits. The Amen Corner (of “If Paradise is Half as Nice” fame) are on stage, and their set obligingly includes a catchy number called “Scream and Scream Again”. However, a few rather too close shots of the singer reveal he’s not even opening his mouth. This club is where Keith picks up his victims, who he then brutally rapes and kills. One of them turns out to be an undercover policewoman, and this leads to the film’s main set piece, an incredibly long but pretty absorbing chase sequence that dominates the whole middle section of the film. This sequence is so lengthy compared to the head-spinning speed of the first part of the film that it throws Scream and Scream Again off balance, with scarcely half an hour left to explain what the hell’s going on. What the hell is going on? Well, I won’t spoil it for you – Scream and Scream Again is definitely worth a watch even if you can’t quite get your head round it. But it all winds up with a glut of exposition from Price (though there’s nobody I’d rather listen to a glut of exposition from) and a pretty perfunctory twist ending.

What the hell is going on? Well, I won’t spoil it for you – Scream and Scream Again is definitely worth a watch even if you can’t quite get your head round it. But it all winds up with a glut of exposition from Price (though there’s nobody I’d rather listen to a glut of exposition from) and a pretty perfunctory twist ending. Marcus and Estelle hook Mike up to the machine, and several minutes of strange noises and a very 1967 light show later, they’re able both to control his actions and feel every sensation he does. Idealistic Marcus has conceived this as a way of allowing old people a new lease of life by letting them share the experiences of the young – and the couple’s initial excitement is rather sweet: the first thing they do is send Mike swimming. But a quick dip isn’t enough, for Estelle at least. Marcus shares the viewer’s horror as it emerges that far from the sweet little old lady she first appeared, Estelle is a monster. Estelle is one of the most frightening characters in any horror film: because she’s one of the most believable. Seemingly kind and gentle, as soon as she’s offered the opportunity to do anything she likes without consequence she seizes it with both hands, gleefully making Mike steal, viciously attack his friend Alan, and finally murder two girls (including anextremely young Susan George). There’s an uneasy message in all this to us, the audience, sat here experiencing all this violence on screen with no threat to ourselves.

Marcus and Estelle hook Mike up to the machine, and several minutes of strange noises and a very 1967 light show later, they’re able both to control his actions and feel every sensation he does. Idealistic Marcus has conceived this as a way of allowing old people a new lease of life by letting them share the experiences of the young – and the couple’s initial excitement is rather sweet: the first thing they do is send Mike swimming. But a quick dip isn’t enough, for Estelle at least. Marcus shares the viewer’s horror as it emerges that far from the sweet little old lady she first appeared, Estelle is a monster. Estelle is one of the most frightening characters in any horror film: because she’s one of the most believable. Seemingly kind and gentle, as soon as she’s offered the opportunity to do anything she likes without consequence she seizes it with both hands, gleefully making Mike steal, viciously attack his friend Alan, and finally murder two girls (including anextremely young Susan George). There’s an uneasy message in all this to us, the audience, sat here experiencing all this violence on screen with no threat to ourselves. Having been denied pleasure for so many years, Estelle’s impulses easily override Marcus’s more benign ones, and he helplessly finds her gaining complete control of Mike. Catherine Lacey’s performance is just incredible: her transformation from meek housewife to blood-crazed harpy is horribly convincing (the highlight perhaps being her queasily post-coital sigh of “that was the best yet” after she forces Mike to beat up Alan). And poor, good-natured, bewildered Marcus is one of the finest performances of Karloff’s career. It’s a real achievement of Reeves and his actors that The Sorcerers’ most compelling scenes consist of two old people talking.

Having been denied pleasure for so many years, Estelle’s impulses easily override Marcus’s more benign ones, and he helplessly finds her gaining complete control of Mike. Catherine Lacey’s performance is just incredible: her transformation from meek housewife to blood-crazed harpy is horribly convincing (the highlight perhaps being her queasily post-coital sigh of “that was the best yet” after she forces Mike to beat up Alan). And poor, good-natured, bewildered Marcus is one of the finest performances of Karloff’s career. It’s a real achievement of Reeves and his actors that The Sorcerers’ most compelling scenes consist of two old people talking.